When Profit and Purpose Become Inseparable

Most social enterprises face a familiar dilemma: impact costs money, and commercial pressures eventually force difficult tradeoffs. Yet Tamul discovered something remarkable. That impact doesn’t need to be a cost center or a marketing claim. It can be the engine of profitability itself.

This isn’t a story about corporate social responsibility or philanthropy with a business attached. This is about fundamentally rethinking how value is created, who creates it, and how returns are distributed.

The Realization That Changed Everything

Early in the journey, Tamul recognized that sustainable impact required two non-negotiable conditions: profitability and integration. Impact couldn’t be a byproduct, something you do when margins allow. It needed to be hardwired into the business model so deeply that the company would pursue it routinely, automatically, even selfishly.

The insight was structural: what if the people at the bottom of the pyramid weren’t just consumers or beneficiaries, but suppliers, producers, and value-adders to products with growing domestic and international markets? What if their success was mathematically required for the company’s success?

The Four Principles That Make It Work

Over the years, Tamul learned four critical lessons that transformed theory into practice.

1. Win-Win Must Be Genuine, Not Aspirational

The relationship between community and company had to be mutually beneficial at all times—not in principle, but in practice. This meant when Tamul earned premiums in export markets, those gains had to flow back to the community.

The mechanism was elegant: differential pricing. For products sold in both domestic and international markets, and produced both in Tamul’s own factory and in community clusters, the company introduced a pricing system where cluster producers earned a premium for every unit that reached export markets. This wasn’t charity or profit-sharing from corporate

earnings. It was built into the commercial structure itself—export premiums generated higher procurement prices, automatically and immediately.

Producers could see the direct connection between the quality they delivered and the premiums they earned. The company benefited from motivated, quality-conscious suppliers. The win-win wasn’t a value statement; it was a transaction.

2. No Freebies, Only Entrepreneurship

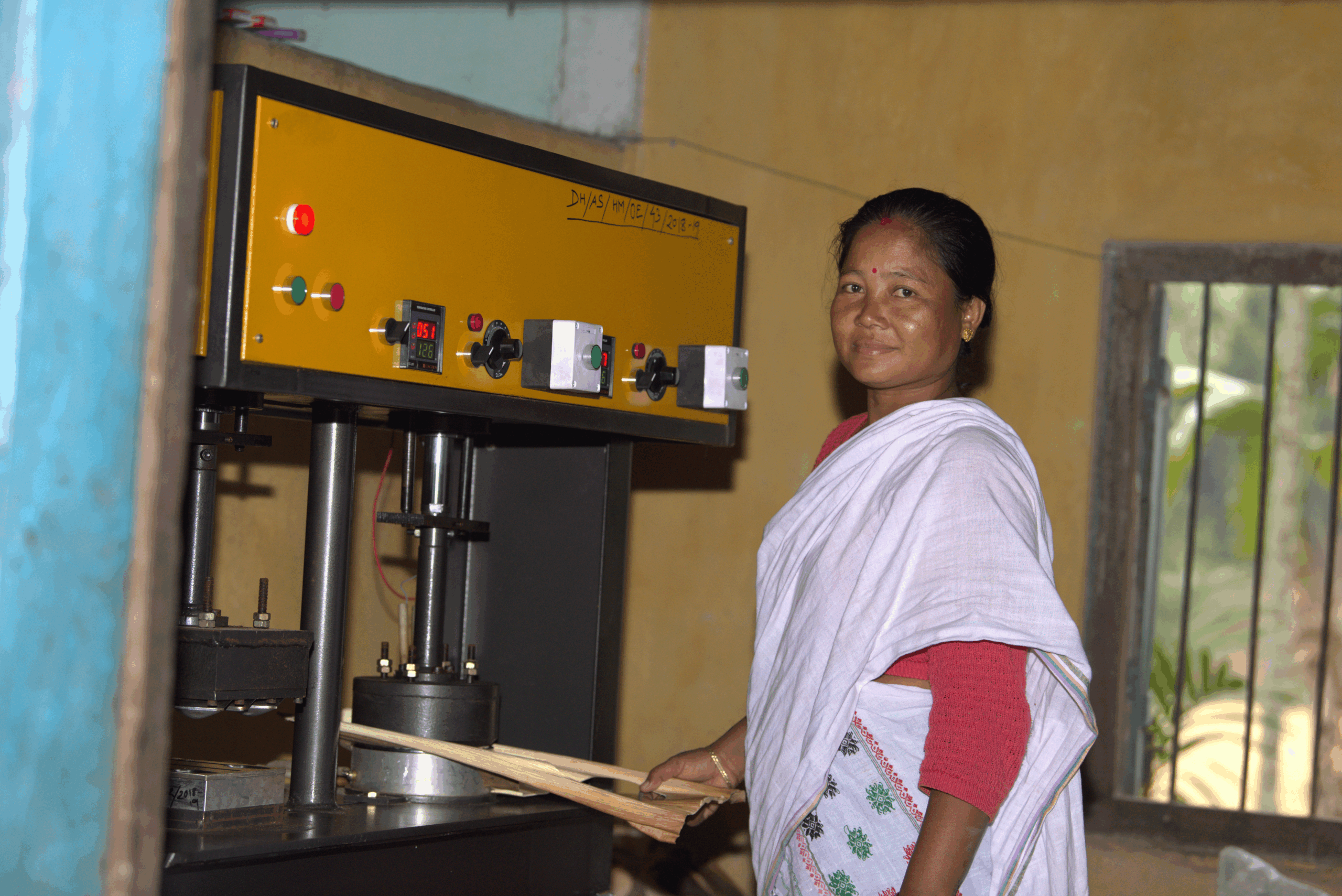

Tamul invested heavily in setting up production clusters—identifying locations, generating awareness, selecting micro-entrepreneurs, providing training, facilitating bank linkages, installing equipment, offering technical support, and guaranteeing procurement. This wasn’t cheap or fast.

But the model had a crucial constraint: no freebies.

Selected entrepreneurs accessed commercial bank loans to set up their units. Tamul supplied machines, technical support, and procurement guarantees but the entrepreneurs owned their businesses through debt, not grants. They had skin in the game.

For banks, this was viable because Tamul’s procurement contracts assured EMI payments. For producers, this created real ownership and accountability they had to produce to repay loans. For Tamul, profit only came when production was procured, which meant the company recovered cluster promotion costs only after production began.

This created a powerful alignment of incentives. It was in Tamul’s direct commercial interest to provide excellent technical services at the doorstep in villages, to offer weekly procurement support at those same doorsteps, and to push for consistent, quality production. The company only succeeded when the entrepreneurs succeeded.

3. From Push to Pull: Order-Based Production

As the model matured, Tamul shifted from procuring whatever clusters produced to an order-based production system. This seemingly simple change had cascading effects throughout the value chain.

Each product manufactured in clusters now had minimal inventory waiting time. Products moved faster from production to market, generating revenue more quickly for the company. Faster revenue meant Tamul could make faster payments to producers, which reduced working capital blockage for everyone involved.

For producers, this meant more predictable cash flow and less risk of unsold inventory. For Tamul, it meant capital efficiency and the ability to scale without proportionally increasing working capital requirements. The entire supply chain became more responsive and less speculative.

4. The Die Bank: Shared Infrastructure, Focused Production

Capital equipment poses a classic barrier to entry for small producers. Dies for manufacturing especially for fast-moving, high-value products represent significant upfront investment that individual micro-entrepreneurs can rarely afford.

Tamul’s solution was to create a die bank: a shared repository of dies for different products that clusters could access without ownership. When an order came in, the relevant clusters were activated, each producer received specific targets that were closely monitored, and the necessary dies were distributed from the bank. Producers didn’t pay for the dies; they simply focused on production. Once the order was completed, dies returned to the bank for the next cycle.

This innovation achieved several things simultaneously. It eliminated a major capital barrier for producers while ensuring they could manufacture high-value products. It allowed Tamul to direct production toward specific products based on market demand rather than what producers happened to have equipment for. And it created a system where the company’s investment in tooling was continuously utilized across multiple production units, maximizing return on that capital.

What This Means for Impact at Scale

Traditional development models often fail at scale because they rely on continued subsidy or goodwill. As organizations grow, the cost of maintaining impact increases while the business case weakens. Eventually, something gives.

Tamul inverted this relationship. Scale increases impact automatically because more production means more livelihoods, more procurement, more premiums flowing to communities.

The order-based production system and die bank innovations show how the model became more sophisticated over time not by adding complexity, but by removing friction. Each improvement made the system more efficient for the company while simultaneously making it more accessible and profitable for producers. Capital efficiency and social impact moved in the same direction.

The entrepreneurs aren’t beneficiaries waiting for the next round of funding. They’re business owners with loans to repay, procurement contracts to fulfill, and premiums to earn. Banks aren’t doing development lending; they’re financing viable credit risks. Tamul isn’t doing charity; it’s securing its supply chain and recovering its investments.

The Working Capital Challenge

Yet one critical challenge for Tamul remains working capital for cluster expansion. In a company where working capital isn’t abundant, cluster promotion budgets often face pressure. Not because the company doesn’t value expansion, but because in the daily reality of business operations, other urgent priorities demand immediate attention.

Cluster promotion is fundamentally a long-game investment. Time and money flow out upfront for location identification, awareness generation, entrepreneur selection, training,

installation, and technical support. Returns only begin after a six-month gestation period, when producers finally start manufacturing and Tamul begins earning from those units alongside the producers.

This creates a cash flow constraint that’s inherent to the model’s structure. The same discipline that makes the model work no subsidies, commercial bank loans, earned procurement also means expansion requires patient capital that can absorb the six-month lag between investment and return. For a profitable but capital-constrained company, this can limit the pace of scaling even when the model itself is proven.

The Broader Lesson

What Tamul demonstrates is that impact and profit don’t need to be balanced they can be the same thing, viewed from different angles. When the bottom of the pyramid isn’t just a market to serve but a production base to empower, when entrepreneurs have ownership rather than dependency, when commercial success requires community prosperity, impact becomes inevitable.

That difference might be the future of how business and development converge not through compromise, but through design.